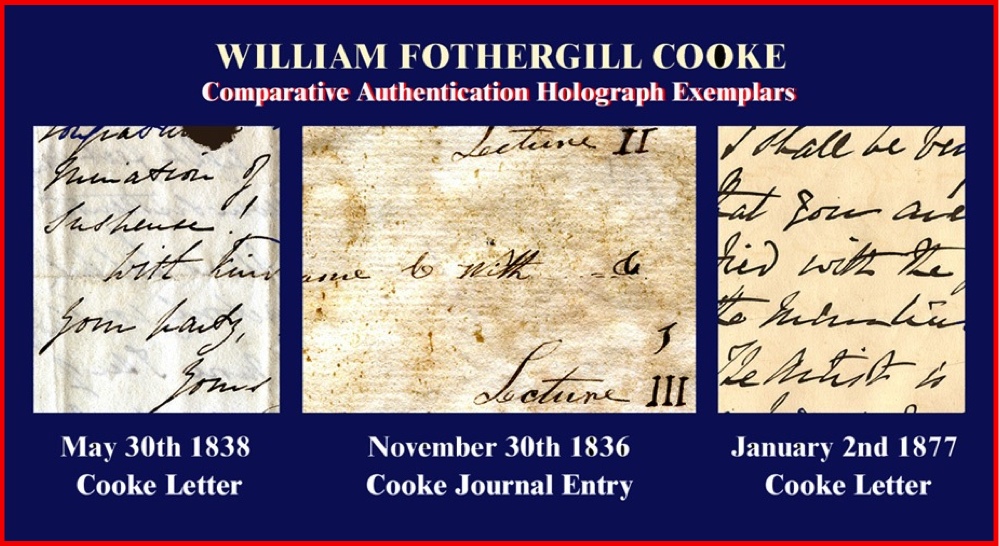

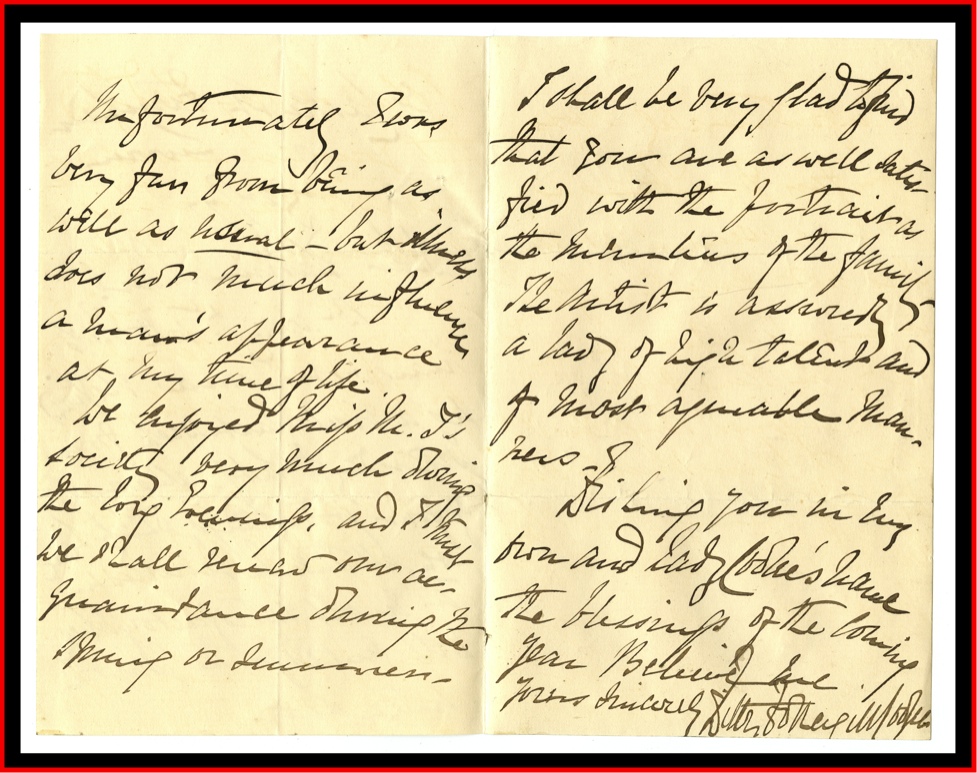

Shown above are handwriting samples executed by William Fothergill Cooke across a span of 39 years that were discovered and acquired by historian Richard Warren Lipack for use as comparative holograph exemplars in the process of paleography that was employed to positively authenticate the 1836-1842 William Fothergill Cooke telegraph manuscript journal.

The center example dates from 30 November 1836 and represents the earliest dated entry in Cooke's journal, i.e. Codex Lipack.

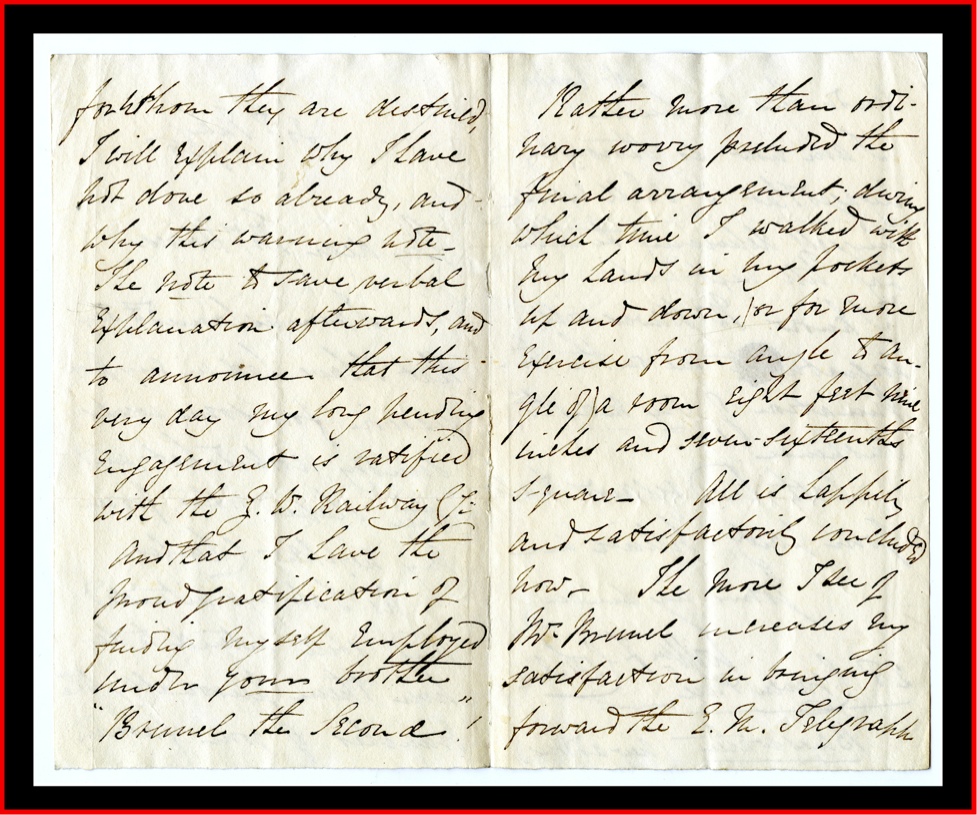

The sample of Cooke's handwriting shown above and to the left dates from 30 May 1838 and is part of a letter Cooke wrote to Mrs. Sophia Brunel Hawes, sister to Isambard Kingdom Brunel - the man on whose Great Western Railway Cooke had installed the world's first permanent telegraph system.

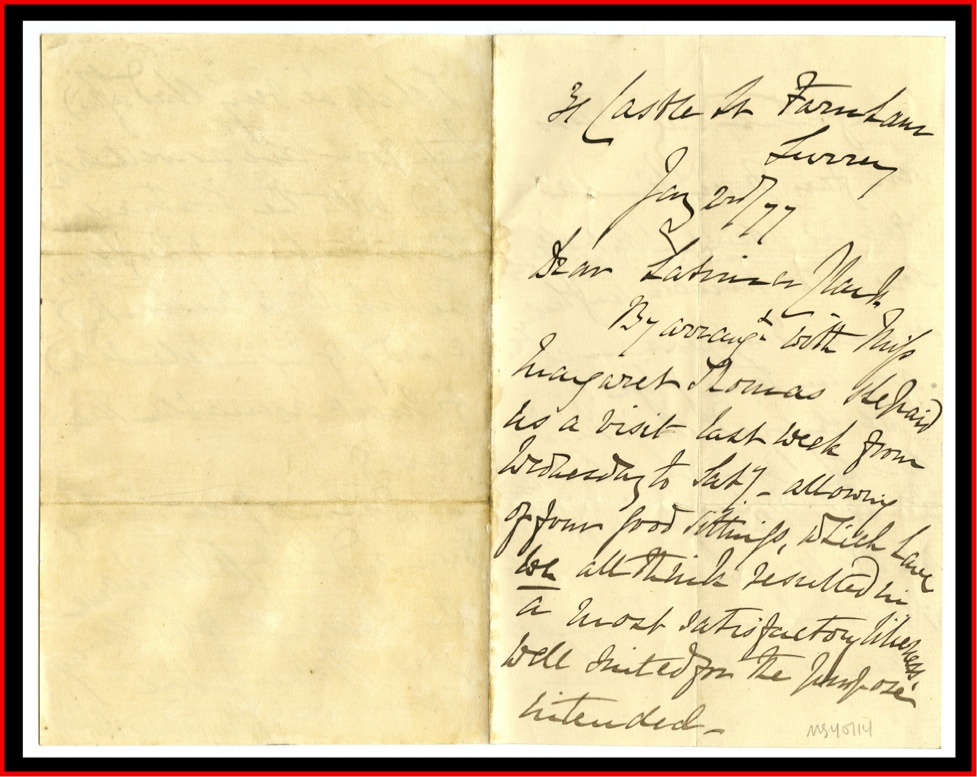

The example of handwriting to the right that dates from 2 January 1877 is from a letter Cooke executed near the end of his life, written to the electrical engineer and telegraph historian Latimer Clark.

Latimer Clark was the most devoted longstanding associate of Cooke's that had worked early-on as a official in Cooke's Electric Telegraph Company not long after its 1846 active formation by Cooke and his business partner and financier John Lewis Ricardo.

The Electric Telegraph Company was the very first public electric telegraph communications company in the world and today is known as British Telecom.

Latimer Clark went on to become a principal in the 1884 formation of the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers, better known as IEEE, to which most of Cooke's early handwritten letters were transferred to via the the gifted purchase of Latimer Clark's huge historical telegraph book and literature collection that the early American electrical motor manufacturer Schuyler Skaats Wheeler provided for. This philanthropic become known as the "Wheeler Gift Collection." That collection today, along with the Cooke letters, now resides in the holdings of the New York Public Library in New York City; after the IEEE organization de-accessioned in the 1990's the lesser common 'garden variety' books and paper found in the collection.

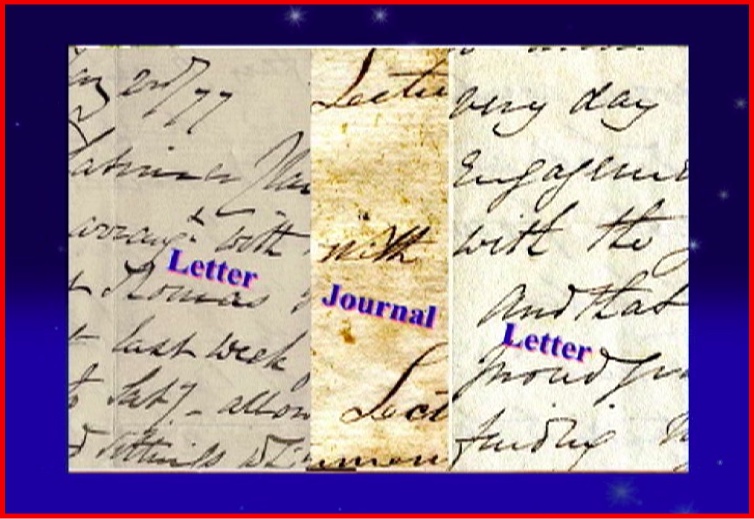

Further addressing again the issue of the Cooke journal's paleographic authentication process, one finds when comparing the word "with" in each of the handwriting samples, as shown hereof, one can plainly and conclusively see that all three examples shown inherently match in particular aspects including that of flow and delineation between "with" specimen exemplar letter entries and that of the word "with" found in the 30 November 1836 journal entry. Hence, one can clearly assert authenticity, establishing that Codex Lipack is in fact Cooke's journal and that the writing within the journal was penned by none other than William Fothergill Cooke himself.

As well, the half a dozen or so signature holograph autographs found on various pages of the journal, too are Cooke's actual bonafide signatures executed by William Fothergill Cooke himself. Several of the addresses penned that accompany some of the various 'Cooke' signatures found in the journal also correspond with known addresses Cooke had maintained. This substanciating fact is based on the large amount of written correspondence Cooke had made to his Mother over the first few years of the time he began perfecting the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph system, where he described the trials and tribulations along the circuitous path he found himself take as his dream of perfecting the telegraph came to fruition.

Getting back to Cooke's letter dated 2 January 1877 to Latimer Clarke, it should be mentioned that Latimer Clark had been a longstanding associate of Cooke's that had worked early-on as a official in Cooke's Electric Telegraph Company not long after its 1846 start-up by Cooke and partner John Lewis Ricardo.

It further should be noted that the Electric Telegraph Company was the very first public electric telegraph communications company in the world and today is known as British Telecom. Close to 190 countries the world over are host to British Telecom offices and operations facilities, making the company the biggest communications company in the world.

Latimer Clark went on to become a principal in the 1884 formation of what has become the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers, better known as IEEE, to which most of Cooke's handwritten letters to Latimer Clark were transferred to its branch office in the United States around 1901 via the gifted purchase of Latimer Clark's huge historical telegraph book and literature collection that Crocker - Wheeler Electric Motor Co. co-founder Schuyler Skaats Wheeler provided for. This became known as the "Wheeler Gift Collection." That collection today, along with the Cooke letters, now resides in the holdings of the New York Public Library in New York City.

The above combined three panels of images represent one of several scenes from the 2 1/2 hour documentary motion picture entitled:

INTERNATIONAL TREASURE: THE LOST JOURNAL

OF WILLIAM FOTHERGILL COOKE

and represents one of several forms of the paleography process

that was employed by Richard Warren Lipack in his

authentication of the Cooke telegraph journal.

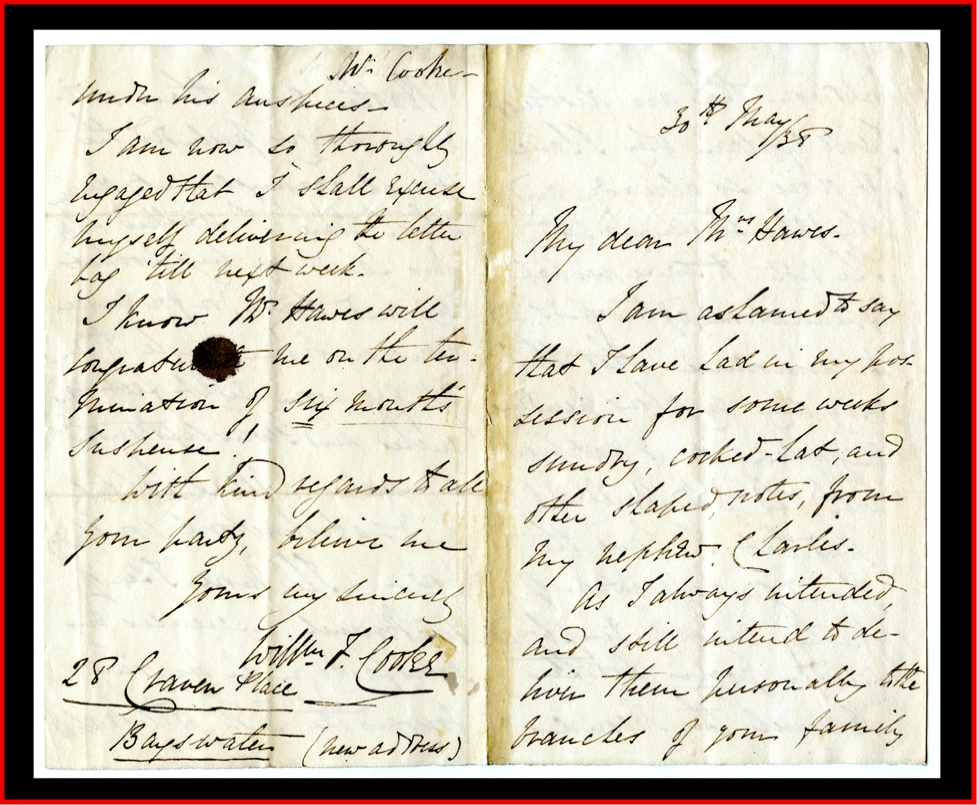

Above and below show the obverse and verso of the 30th May 1838 Cooke letter written to Sophia McNamara Brunel Hawes, sister of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, discussing his frantic wait and finally to hear of Brunel's positive decision concerning Cooke's first telegraph deal with the railroad and bridge building tycoon.

Not long after Robert Stephenson's London and Birmingham Railway rejected a trial installation of the Cooke and Wheatstone system, William Fothergill Cooke approached another prospective railway.

In following, Cooke wrote about this new effort to Sir Benjamin Hawes' wife Sophia Macnamara Brunel Hawes, on May 30th 1838. Cooke revealed the propitious meetings he had with Mrs. Hawes' brother Isambard Kingdom Brunel, of the Great Western Railway.

Cooke expounded about the contract he had just signed with Mrs. Hawes brother that ultimately allowed for Cooke to now set-up shop along Brunel's Great Western line with the Cooke and Wheatstone system.

The success of this installation subsequently led to the London and Blackwall Railway telegraph installation of 1840, which would become the first perfected commercial electric telegraph system in the world that July.

The 1838 Cooke letter amusingly reads in part;

"… and to announce that this very day my long pending engagement is satisfied with the Great Western Railway Co. and that I have the proud gratification of having myself employed under your brother "Brunel the Second"! Rather more than ordinary worry precluded the final arrangements during which time I walked with my hands in my pockets, up and down, or for more exercise from an angle to angle of a room eight feet nine inches and seven sixteenths square. All is happily and satisfactorily concluded now. The more I see of Mr. Brunel increases my satisfaction in bringing forward the E. M. [Electric Magnetic] Telegraph under his auspices. "

In this particular entry, over a century and one half later, William Fothergill Cooke provides today's historians such uncanny details into the machinations he endured as a poor young inventor in his quest to bring about electric magnetic telegraphic communications to the world.

Here, confined to a tiny cramped room measuring only about 9 feet by 9 feet square - Cooke had just enough room for a small wardrobe chest, perhaps a table to draw and write on in his journal to show Kerby the machinist his latest telegraph designs, and too, on which he could write his mother his ongoing letters. And certainly he had a chair to sit on to do all of this as well with some assembly of comfort. The luxury of a small night stand beside the bed too, may have been in place. Of course, there was likely a communal toilet perhaps down the hall. He was a Londoneer and certainly could enjoy a bath and the cheer of running water.

And amid all of these bare essentials crammed into his tiny cramped 'abode' Cooke nevertheless exuberantly shared his excitement with Mrs. Sophia McNamara Brunel Hawes, that he had just consumated his first deal with The Great Western Railway and her brother "Brunel the Second" - the greatest industrialist of the early part of the 19th century! Eventually, although not much further away on the horizon, little did Cooke fully realize he would become successful with his telegraph and when that time would come, he would no longer need to get funds sent to him from his Mother to in order to subsist!

PALEOGRAPHY PROCESS UNDERTAKEN

TO AUTHENTICATE THE COOKE JOURNAL

Here, above and below, in this 2 January 1877 letter to Latimer Clark, a now aged William Fothergill Cooke, at the later part of his life - discusses Margaret Thomas, the little known female portrait painter coming to paint his oil portrait, apparently the only one Cooke appears to ever have sat for. It was at a time when Cooke was near penniless and had lost

his entire fortune derived from the telegraph.